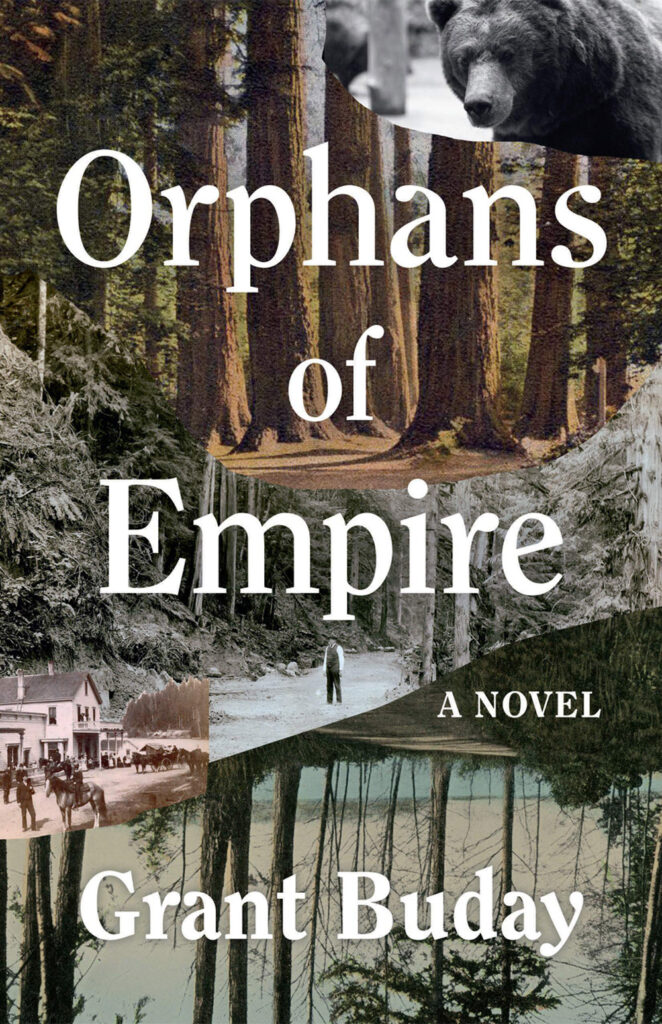

Author: Grant Buday

Touchwood Editions, 2020

First Edition; 272 pages; $22.00

ISBN: 197366909

Dave Flawse

Laced with tenderness and humour, Grant Buday’s Orphans of Empire weaves three mid-nineteenth century frontier stories into a gritty and desolate tale of British Columbia’s lesser-known history.

The trio of story threads span three decades beginning with Moody who eventually establishes Brighton Beach on Burrard inlet. Although the three protagonists never meet, their shuffled story threads speak to one another in proximity.

Most of the narrative takes place on the Mainland, but the city of Victoria plays enough of a starring role to include it on this blog.

The Queen city is where Moody, the book’s only real-life historical main character, meets with Sir James Douglas after first arriving from England via the Panama Canal.

Moody’s intricacies—a desire to please his deceased father, and by extension Governor Douglas, mixed with an inferiority complex—parallels those of the burgeoning colony, a place on the far reaches of the world with one foot back in the fatherland and the other in BC where expectations are high, and resources limited.

The narrative of Buday’s second protagonist, Popo, is cast in first-person which forces the reader to live her oppression (as a victim of both racism and sexism) even as she perseveres against those who see her as their servant.

In contrast to Moody’s conversations, hers show us a much less elite and rarefied world. Her desire to be in charge clashes with societal expectations, providing a tension-rich narrative and leaving the modern reader to consider what has—and hasn’t—changed today.

As a love-struck eccentric and dead-body buff, the third protagonist, Fannin, faces oppression of his own, which he confronts with similar bravado and tenacity. His obsessions hurtle the story forward and will invest you in his tale of love and self-discovery.

Popo and Fannin represent the lower rungs of society while Moody is the aristocrat and British subject who believes in the Empire but endures “the now familiar ache of a deep-seated doubt” about his contemporaries’ belief that their work in the colonies would improve the lives of Indigenous Peoples.

Despite his doubts, he admits that “the momentum of Empire could not be slowed. Stand in the way and you were ground to gravel like rock under a glacier.” Buday uses Moody’s mixture of passive and pragmatic to help the reader relate to Moody without letting him off the hook for his role in colonizing the West Coast.

The characters in Orphan’s of Empire are as nuanced as this province’s history, and while the three stories do come to their own resolutions, this reader wanted more of a connection between the characters.

Without a doubt this book is worth reading, but I would encourage you not to fixate on the word “novel” on the front cover and instead approach it with the expectation that it’s three novellas connected through place and theme.

That said, Buday’s mastery of time-appropriate voice will pull you into the time period. His character and setting details will earn your trust and confidence in the depth of his research.

Buday takes all the things we love about fiction and tosses it with well-researched history to create an easily digestible way to consume these important tales. The book is a service to BC history and relevant to contemporary discussions around Canadian dinner tables today.