Dave Flawse

Harbour Publishing

ISBN: 9781550179750

Hardback

6 in x 9 in – 360 pp

Publication Date: 28/05/2022

This review was also published in The Canadian Journal of Native Studies.

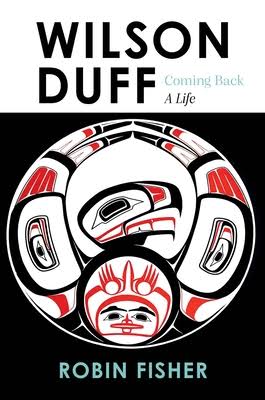

To appreciate Wilson Duff’s biography, you need not know who he was—Wilson Duff Coming Back, a Life is about more than just one man. People that knew Duff called him a genius. He had a mathematical mind and a poetic one. Consequently, his life, and by extension this biography written by Robin Fisher, reveals a mosaic of life-long learning.

Throughout Fisher’s 360-page odyssey you will glimpse depression-era Vancouver; examine air navigation and the mental strains of war; witness the evolution of anthropological studies; discover the history and theory of Northwest Coast Indigenous art; and be amazed at how Duff was a part of it all in his own, unique way.

Wilson’s daughter, Marine Duff, wanted someone to tell her father’s story in full to “replace the fiction and academic gossip” out there. Fisher agreed to take on the book because, “I simply think this is a story that needs to be told.” I agree with him here. Duff’s life (1925-1976) is full of rich intrigue in writings that influenced a generation of anthropologists, including Fisher himself.

Robin Fisher is the author of Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, one of the first BC books to provide an extensive analysis of Indigenous-settler history. The book was first published in 1977 by UBC Press and is one of the most successful academic titles in the province. That book arose from Fisher’s PhD dissertation at UBC where Duff was his supervisor. After seeing Duff’s comments on a paper, he realised Duff’s mind “was going in directions different than anyone else in the room.”

Fisher dedicated Contact and Conflict to Duff because he had such a huge influence on his thinking. Contact and Conflict covers up to the year 1890, and some have asked Fisher whether he would continue the history in a second volume. This biography, says Fisher, “might be seen to be a partial answer to that question.” However, reading Contact and Conflict is not a prerequisite to understanding Duff’s biography.

Through a concise and clear writing style, Fisher illuminates one of the great mysteries in this book: why did Wilson Duff take his own life? (One other mystery is the “Final Exam” which Fisher explains in detail, but I won’t spoil here.) We know from the beginning how his life will end, so, as a reader, I hung onto any mention of Duff’s mental state. Though that is only one aspect of this multifaceted story, it is ever lurking in the background.

The biography follows Duff’s life milestones in a neat chronological thread with chapter titles like Vancouver Boyhood, Learning Anthropology, Restoring Totem Poles that clearly tell the reader what to expect. The more obscure chapter titles like I, the Navigator and Negative Spaces offer some of the book’s most unexpected moments. The former is a glimpse at WWII Canadian bomber crews in India, where Duff lived on a base and attacked Japanese positions in Southeast Asia. As a squadron lead navigator on a Lancaster bomber, Duff was not only responsible for getting his plane over enemy territory and back, but all the planes in his squadron—he was 19 years old.

After the war, Duff enrolled at UBC where, in parallel with many students’ trajectory through university, he ended up with a degree in a completely different field than he had anticipated from the start. With his analytic and creative mind, he fell in love with the ethnographic side of anthropology.

After achieving a master’s degree in 1950, Duff became a permanent employee of the BC Provincial Museum. Though not his job title, at only 25 years old, he was effectively the provincial anthropologist. Fisher explains that over the ensuing years, Duff worked closely with various First Nations, becoming “a bridge between two cultural islands separated by a sea of ignorance.”

It’s important to note that Duff’s beliefs were often ahead of the time. Fisher says, during the mid-20th century, a time when Indigenous people “were not encouraged to speak and were seldom heard by settler society, Wilson was listening.” In the decades before this time, settler ignorance led to private collectors and museums stealing and acquiring totem poles and other artworks from First Nations across the Pacific Northwest, leaving little work remaining in communities. Duff sought permission from various First Nation communities to preserve what remained by taking it back to Victoria. Fisher says, “He took some poles down so that many could rise again.”

And this is where things get a little messy. Through today’s lens, much of Duff’s work is seen as cultural appropriation. And even back then, Duff could see how taking these artworks and putting settler meaning on them was troublesome. These subtleties in the complicated history between Indigenous Peoples and settlers are part of what makes this book so great. Through Duff, Fisher is able to show the many sides to our shared history—the good and the bad.

For his work preserving totem poles, Duff was given the Haida name gwaaygu7anhlan. The name belonged to Albert Edward Edenshaw, a Haida artist whom Duff, later in life, believed he had a close connection to.

Wilson Duff spent 15 years as the provincial anthropologist. However, all of his success and hard work came at the cost of his family life. And tensions became exacerbated when the family uprooted to move across the Salish Sea when he got a teaching gig at UBC. Students at UBC loved his teaching methods. According to Fisher, “it seems as though a whole generation of students took Wilson’s Anthropology 301.” Duff assigned readings to his students like Alan Fry’s How a People Die, a novel based on the forced relocation of the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Peoples. I wrote about a ‘Nakwaxda’xw hereditary chief’s efforts to revitalize almost lost traditions here.

Fisher argues that Wilson Duff surpassed the ordinary range of human experience in his analyzing of Northwest Coast art, especially the art of his namesake, Albert Edenshaw. He seemed to transcend into a state of mind where very few could reach. However, there was a dark side, as Fisher points out, “As he was consumed by a burst of highly creative thinking about meaning in Haida art, Wilson was slipping through the formlines into negative spaces.” The end of the book features a suicide, and that is naturally disturbing, but Fisher’s cause and effect explanation to what led to it takes an unexpected turn at the end.

This book is well worth the purchase. It’s a story well told that carries us through the deep waters of Wilson Duff’s mind where we stay only on the surface yet can glimpse down and understand these waters are bottomless.