Dave Flawse

At the turn of the twentieth century, a would-be investor in Victoria, BC sat down with his morning coffee and opened a booklet entitled There’s Money for You in Perez Park.

An introductory note for this land-investment guide warned that similar investment guides seek to mislead investors with “glowing and extravagant terms,” but not this booklet. This booklet contained only “authentic facts.”

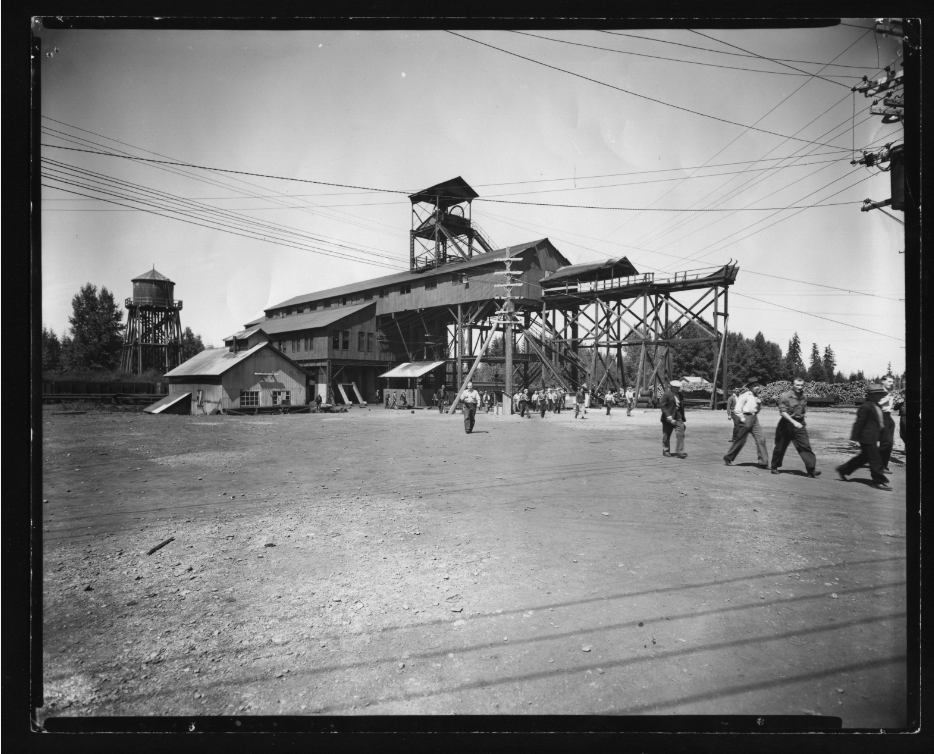

Far up Island near a townsite named Puntledge in the Comox District, Canadian Collieries (Dunsmuir) Ltd. sunk a 1000ft shaft into the earth and constructed a hydro-electric dam on the nearby river to power its all-electric tools—state of the art for 1912.

The total cost of building the mine in 1912 ran around two million dollars—almost 50 million dollars today—and real estate speculators like the Perez Park Syndicate became understandably excited at the prospect of a flourishing new community in the area.

The booklet promised, “900 men with their wives and family,” would be working at the mine, equalling “a total of 2,700 to feed, clothe and provide for” and a further 2,000 people would be needed to provide support services for this population.

Along with these optimistic claims the booklet exalted the soil in the region as “chocolatey” and the mild weather permitted “flowers grown out of doors on the table on Christmas day.” (Perhaps a hearty variety on an El Niño year.)

Pictures in the booklet depicted homes recently built on Perez Park, and a railway crossing at a nearby road. However, these went beyond an embellishment of facts. At Perez Park only a field of stumps stood, and the photos in this “authentic booklet” had been taken at other locations around the Comox Valley.

The Park’s namesake is likely a homage to Juan José Pérez Hernández, an eighteenth-century Spanish explorer who was the first known European to record island names on the BC coast in 1774. A sign at a small nature park in Victoria takes its name from the same man.

More than one investment syndicate sold lots around the mine. One racist investment advertisement for “Berwick No.8 Townsite” read, “It’s the white man’s city. We do not sell to Asiatics.” Perhaps this was a marketing decision to separate itself from Perez Park (which made no such claim).

None of this grotesque market postering and embellishing would matter, anyways. Two years later, the mine failed meet all the promises of the booklet.

In six hours workers could haul almost 1,000,000 tons up the elevator to the surface, and with the first loads, equally heavy news came—the coal wasn’t as clean as the borehole had indicted. The No. 4 coal seam at the 1000ft level “had wide bands of dirt in its makeup making it almost impossible to mine a clean product,” according to Bill Johnstone in his memoir, Coal Dust in my Blood.

Without official announcement the company discontinued operations at the Number Eight mine. Workers removed the elevators and let water fill the shaft. For workers earning around 1000 dollars per year, the shut down seemed incomprehensible, and from then on, the mine became known as the Million-Dollar Mystery.

The mine sat dormant as the tragic war in Europe came and went followed by a pandemic that ripped across the globe. Over two decades after it closed and on the precipice of another world war the mine opened again.

In 1936, 400 miners worked the higher quality No.2 seam at the 700ft level. A townsite around the mine never materialized, and the workers rode the train from their homes in Cumberland to work and back everyday.

For nearly 20 years the mine operated until the market for coal diminished. On a dreary February day in 1953, a mine worker loosened the last bolt holding an elevator above the 1000ft shaft at the Number Eight mine. It plummeted a few hundred feet before splashing into the water that had begun filling the mineshaft after the crews hauled anything of value out.

Bill Johnstone had worked the mine for decades and before that worked in mines in Britain since he was fourteen years old. He eventually became the general manager of Canadian Collieries and supervised as a crew poured a two-foot-thick slab of reinforced concrete over the gaping shaft. After that, they torched through the four supports of the steel structure on each corner which held the elevator.

You can visit the site now and see the concrete slab and the torched supports. The site is a popular spot for visitors and partiers. Some call the graffiti covered monuments Drac’s castle because of the ominous concrete arches that resemble a gothic vestige. Though, another site in Merville also sports the name, so it’s unclear which is which.

Whatever the name, few who stand on the slab at Number Eight Mine, I imagine, are aware they are standing above 1000ft of empty space below, held from a ten second freefall— just enough height to reach terminal velocity—by a relatively thin slab of 70-year-old concrete. Though, the shaft is likely full near to the top with water as back in the day electric pumps worked around the clock to remove water from the mining area.

Who knows whether that would-be investor in Victoria would have been persuaded to buy in Perez Park. The investment wouldn’t have made him money, but his great grandchildren would have seen big gains. The lots in 1912 sold for around $150. Lots in the area today are worth around half a million.

And with climate change warming our winters it’s becoming more likely you could grow flowers out of doors and display them on the table at Christmas—Perhaps Perez Park was merely ahead of its time.

Sources:

Johnstone Bill, Coal Dust in My Blood (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1980) 143.

Isenor, D.E., E.G. Stevens, and D.E. Watson. One Hundred Spirited Years: A History of Cumberland (Campbell River: Ptarmigan Press, 1988) 75, 80

Authentic Facts and Photographic Views of Perez Park (The Perez Park Syndicate of Courtenay, B.C., 1912. From the Cumberland Museum Archives File: MNF.012.001 No. 8 Mine)

Berwick No.8 Mine Townsite (From the Cumberland Museum Archives File: MNF.012.001 No. 8 Mine)

Number 8 Mine Airshaft Hoist (From the Cumberland Museum Archives File: MNF.012.001 No. 8 Mine)